It was 1910, or maybe 1911 or 1912, when Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish-born antiquarian, purchased a strange, medieval manuscript.

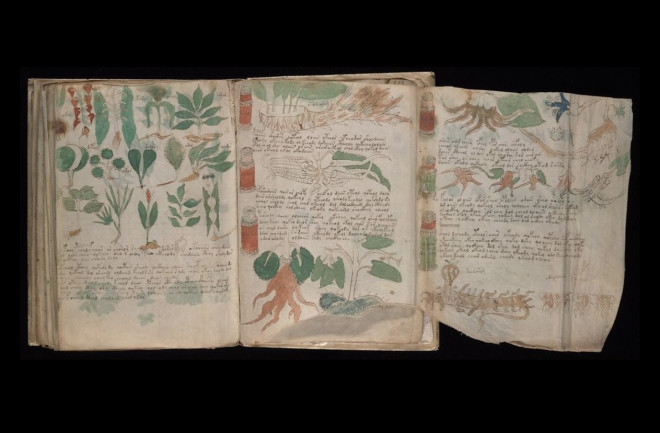

Similar in size to an average paperback, at around 6 inches by 9 inches, the book burst at the seams, brimming with words and pictures of peculiar plants, strange stars, and bathing female figures. At around 232 pages, the book bore no indication of its authors and lacked the luster — and the metal leaf — seen in many manuscripts from the “illuminated” age. Increasing its intrigue, its writing was wholly incomprehensible, causing Voynich to conclude that the tome was written in code.

That’s the traditional story told about the “Voynich Manuscript,” acquired in a Jesuit archive outside of Rome. But what are modern researchers actually revealing about the text, commonly considered the world’s most mysterious manuscript? Is the tome a true artifact of the Middle Ages, or is it a mere forgery — a medieval or a modern fraud?

Read More: The Mystery of Extraordinarily Accurate Medieval Maps

What Is the Voynich Manuscript?

Said to trace its origins to the 1400s, the Voynich Manuscript is an illustrated manuscript that continues to mystify medievalists and confuse cryptologists centuries after its supposed creation. Taking its title from the antiques aficionado who allegedly acquired it in the 1910s, the tome came from the then Jesuit-owned and occupied Villa Mondragone in Italy, from a collection of 380 medieval manuscripts, all set for future sale.

What’s Inside the Manuscript?

Wrapped in vellum with vellum pages, the manuscript features 116 folded folios bound in 18 bundles. The binding of the book is old and busted, though it is not original to the text. According to an analysis of the tome in the 2021 Annual Review of Linguistics, many of the pages are foldouts, while many more are missing, adding to the manuscript’s overall mystery.

The Voynich Text

Inside the tome are innumerable lines of looping text, inked in iron-gall ink — a medium typical of the Middle Ages. Scribbled in a strange, unfamiliar language and a strange, unfamiliar script, the text’s linguistic system is sometimes labeled as Voynichese.

Like Voynich, many modern scholars suspect that the manuscript’s text is a ciphered form of a familiar language, with their theories of the tome’s latent linguistics flitting from Latin to Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs and Toltecs of Mexico. Others say that the text is an artificial language or strange shorthand, and others still see the text as meaningless scribbles. The theories of the tome are, thus, all over the place, with no one opinion snagging widespread support.

The Voynich Images

Alongside the text — whether meaningful or meaningless — are an abundance of illustrations. Composed of colorful inks and pigments in tones common to the 1400s, these illustrations seem to split the manuscript into four separate sections — including sections about botany, astronomy and astrology, balneology, and pharmacology — as well as a fifth and final section, unillustrated, with blocks of text separated by stars.

The first and most substantial section of the manuscript, the botany section, contains detailed drawings of plants. The astronomy and astrology section that follows features illustrations of the stars, the sun, and the moon alongside several zodiac signs. Immersed in strange, shared baths, female figures frolic through the pages of the text’s balneological section, while the pharmaceutical section is packed with what appear to be medicinal plants, thanks to the inclusion of medicinal bottles throughout the illustrations.

Read More: Just How Dark Were the Dark Ages?

Who Wrote the Voynich Manuscript?

Next to nothing is known about the authors behind the manuscript, whose motivations for compiling the codex are also mystifying. And muddling the manuscript’s authorship further is the fact that the tome may be based off of another text. “We do not know whether the extant physical codex was copied from some earlier source,” the authors of the 2021 Annual Review of Linguistics analysis, Yale University linguists Claire Bowern and Luke Lindemann, assert in their article.

What Was the Voynich Manuscript About?

Though Voynich considered the text a tome of “natural philosophy,” crediting its creation to the philosopher Roger Bacon, many modern interpreters take the text as medical, with the plants and female figures representing recommended remedies and treatments. But this interpretation is not without its issues: In a 2021 interview with Knowable Magazine, Bowern mentioned that the majority of medicinal works from the time were written without ciphers or codes, making the meaning of the tome all the more mysterious.

In 2022, in an article for the inaugural International Conference on the Voynich Manuscript, a Macquarie University researcher pointed out that the female figures inside the tome tend to appear alongside objects “adjacent to” or “pointed towards their genitalia,” an indication that the text could contain gynecological insights. Citing ciphered or otherwise concealed sources from throughout the Middle Ages, the researcher, Keagan Brewer, asserted that the medieval fear and taboo surrounding female anatomy is “worth considering” in the context of the Voynich authors, though far from conclusive in revealing their motivations.

Who Owned the Voynich Manuscript?

Despite their dearth of knowledge about who made the manuscript and why, scholars are slowly parsing out the manuscript’s previous owners. Some say, for instance, that one of the first owners of the manuscript was Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, who reigned over a substantial stretch of Europe from 1576 to 1612. Though it is unknown when and where Rudolf II obtained the manuscript, an inscription inside the tome suggests he passed the text to his personal pharmacist and physician, Jacobus Sinapius, during his reign.

Presented to the other Holy Roman physicians over the ensuing years, the tome eventually entered the library of the Jesuit philosopher Athanasius Kircher, to whom the text was already mystifying, as “some sort of mysterious steganography,” in 1666. From there, it is likely that the tome traveled to Villa Mondragone. Today, the text belongs to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

Read More: Science Was Alive and Well in the Dark Ages

Is the Voynich Manuscript A Hoax?

That the manuscript is still so shadowed in terms of its authorship, its purpose, and its past has supported several theories that the text is a hoax. In fact, since the finding of the manuscript in the 1910s, some scholars have suggested that the manuscript is mere gibberish — made in medieval or in modern times to look like a ciphered, constructed, or natural language — while others have said that the work is an authentic medieval article, written in a legitimate form of language that’s simply too difficult to decode.

To this day, scholars still wrangle over whether the manuscript is a hoax or not, though several lines of evidence, including the provenance and the material of the manuscript, are starting to suggest that the tome — gibberish or not gibberish — traces to medieval times. Even the overall thickness of the text exposes the tome’s manufacture, making it more and more likely that the tome is at least partially meaningful, whether that meaning will ever emerge.

The Provenance of the Manuscript

The first indication of the manuscript’s medieval origins is its provenance. Of course, the manuscript’s long line of owners — from Holy Roman Emperors to Jesuit learners — lends to its credibility as a medieval artifact. That said, Voynich’s interest in shrouding the manuscript in mystery is sometimes seen as a sign that the text is a modern forgery, its illustrious owners being nothing more than mere invention.

To be sure, the manuscript’s acquisition is steeped in secrecy, and Voynich was famously reticent about when and where the tome was recovered. This reticence is sometimes interpreted as an intentional move by Voynich, meant to conceal the manuscript’s modern creation.

That the manuscript’s provenance is spotty could support the theory that the tome is modern. But recently, more and more scholars have suggested that Voynich had other motivations for hiding the manuscript’s history. Having obtained the text under dubious circumstances — the book had been bundled in a collection of manuscripts set to be sold to the Vatican — Voynich may have been reluctant to reveal its true origins. Thus, they say, it is likely that the manuscript was truly medieval despite the shadiness of its discoverer.

The Material of the Manuscript

The second indication of the manuscript’s medieval origins is its material make-up. In 2009, samples from the manuscript were radiocarbon dated, revealing an approximate date between 1404 and 1438. “We assume that the manuscript is a genuine medieval object and not a modern forgery,” Bowern and Lindemann assert in their 2021 analysis, citing the carbon dating, as well as the manuscript’s “overall appearance” as an artifact from the Middle Ages.

“Those who argue that the manuscript is a modern hoax must assume that Voynich (or another person) obtained a large amount of untouched medieval parchment and made ink highly consistent with medieval practices,” the linguists add in their article. “They must anachronistically assume that a modern hoaxer was trying to prevent detection by circumventing tests that had not, at that point, been invented.”

The Size of the Manuscript

Also revealing the origins of the manuscript is the sheer size of the tome, which seems to suggest that the text is meaningful. Requiring an abundance of raw material and time to compile, some scholars suspect that there were several scribes — as many as four or five — who worked on the manuscript, shaping the symbols of Voynichese with slight variations throughout the tome.

“We also consider it unlikely that the Voynich Manuscript is a medieval hoax,” Bowern and Lindemann affirm in The Annual Review of Linguistics. “The cost associated with the production of such a manuscript and the number of people involved make it unlikely that it was created purely to deceive. A much smaller hoax would have served the same purpose at much less expense.”

Read More: Modern Medicine Has Its Scientific Roots In The Middle Ages

Linguistic Theories of Voynichese

Perhaps the most promising tools in the mission to translate the Voynich Manuscript are the techniques of modern linguistics. Applying some of the same statistical approaches that they apply to familiar languages, linguists are starting to study Voynichese alongside languages like Latin, Arabic, and Hebrew — ciphered and unciphered — to understand its underlying linguistics.

Word- and Section-Level Insights

At the word level, for instance, Bowern and Lindemann’s analyses indicate that Voynichese is distinct from familiar languages, in that the occurrence and order of letters is much more predictable than it is in familiar languages. (This predictability, Bowern and an associate add in a subsequent article from 2022, is typical of intuitively generated gibberish, made to mimic “what written language ought to look like.”) But beyond the word level — at the level of large sections of text — Voynichese is, in fact, similar to familiar languages.

As with writing in any familiar language, the separate sections of the Voynich Manuscript show a certain clustering of words according to their topics: There are words in the manuscript that only appear in the botanical section or the pharmaceutical section of the manuscript or so on, Bowern said to Knowable Magazine in 2021, making the text look a lot like meaningful language.

As such, imbued in the tome are the statistical signs of meaning and of mischief, appearing simultaneously, side-by-side. “A remaining possibility is that the VMS (Voynich Manuscript) encodes meaningful information, but it is concealed by steganography within a larger body of gibberish,” Bowern and Daniel Gaskell, another linguist at Yale University, assert in their 2022 article. “However, we leave this intriguing possibility for future researchers.”

Language Identification

Thus, linguists still aren’t sure of the text’s structure, though they aren’t the only ones. In the past ten years, scholars from an assortment of fields, from linguistics to language processing to biology, have claimed to have cracked the code of the Voynich text, only for their claims to be swiftly challenged and contradicted. “All current language claims are clearly problematic,” Bowern and Lindemann conclude in The Annual Review of Linguistics. “Nonetheless, there is a lot to say about the language” — namely, that there’s a lot more to learn.

Read More: How Medieval Europe Finally Ditched Roman Numerals