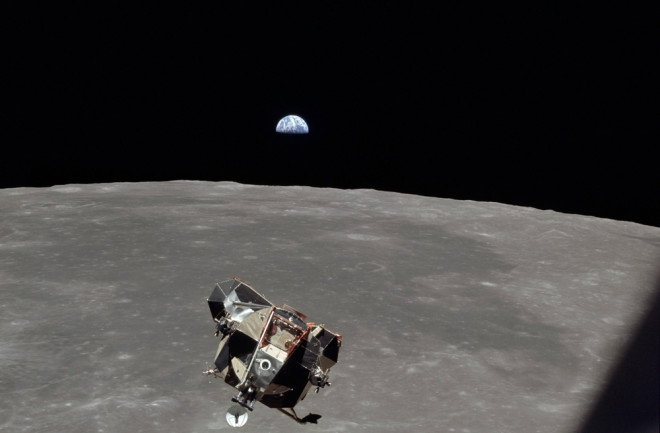

On July 21, 1969, Apollo 11’s Eagle lunar ascent stage lifted off from the surface of the Moon to rendezvous with the command module Columbia in orbit. After docking, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin clambered back into Columbia carrying 22 kilograms of lunar rock. The crew then closed the hatch and the command module returned to Earth.

Before leaving, though, it jettisoned Eagle, leaving the ascent module in a retrograde orbit some 125 kilometers above the lunar equator. NASA has always assumed that this orbit was unstable and that some time later, Eagle must have crashed into the lunar surface.

Now, a new analysis suggests that Eagle is still up there, in essentially the same orbit that Columbia left it in. “There exists some possibility that this machine might have reached an inert state, allowing it to remain in orbit to the present day,” says independent researcher James Meador. Indeed, the spacecraft might still be visible from Earth to anybody willing to look hard enough to find it.

Planetary geologists have long known that the Moon’s mass is not evenly distributed throughout its volume. Instead, underground concentrations of mass lead to tiny variations in the Moon’s gravitational field that make most lunar orbits unstable in the long term.

In 2012, NASA sent a pair of spacecraft called GRAIL to map the Moon’s gravitational field and this mission eventually created a detailed map of this varying field.

That gave Meador an idea. Nobody knows what happened to Eagle after NASA abandoned it. So why not use this map to work out how Eagle’s orbit must have decayed and where it might have eventually hit the lunar surface. That could point observers to the impact crater that is Eagle’s final resting place.

Deliberate Crashes

By contrast, the lunar ascent modules from Apollos 12, 14, 15, 16 and 17 were all deliberately crashed into the Moon to help calibrate seismometers that astronauts had left on the surface. Apollo 13 astronauts famously used their ascent module as a lifeboat to get back to Earth, where it burnt up in the atmosphere.

Meador began his task using an open-source program called the General Mission Analysis Tool developed by NASA and others. This models a spacecraft’s trajectory in any gravitational field and is widely used to simulate missions to Earth orbit, to the Moon, to Mars and beyond.

Meador loaded the program with GRAIL’s lunar gravitational field and then used it to work out what must have happened to Eagle after Columbia jettisoned it in 1969. The program models Eagle as a uniform sphere and includes the effect of numerous, small but relevant forces such as the gravitational pull of the Earth, the Sun and all the planets except Mercury.

At each point in time, it calculates the effect of all these forces to determine where the spacecraft will be at the next point in time and then repeats. In this way, it calculates how a spacecraft’s orbit changes over time.

It can even include the effect of solar radiation pressure. By running the program with and without this force, Meador found that this had little effect on Eagle’s orbit. Of course, this stability could be the result of the particular set of starting parameters for the spacecraft in the program — the time of jettison, the latitude, longitude and altitude, heading angle and so on. So Meador changed these parameters by small amounts to see what effect this would have on the long term stability of the orbit. Using 100 different random combinations of these parameters, “all results showed similar behavior,” he says.

Exploding Fuel

To his evident surprise, this implies that Eagle’s orbit is not unstable as had been assumed.

“These numerical experiments support the hypothesis that even with the uncertainty of the initial conditions, the true orbit of the Eagle exhibits long term stability, and the spacecraft would not have impacted the Moon due to gravitational effects,” concludes Meador.

However, the lunar module may have succumbed to other problems, given that it was designed to operate for a mission lasting only 10 days. For example, unburnt fuel can leak or explode. There are well documented cases of defunct satellites and spent rocket stages exploding in Earth's orbit when unspent fuel ignites. Eagle could have succumbed to a similar fate.

But if it has survived, then the spacecraft should be observable today, says Meador. Back in 2009, the Indian Space Research Organization lost contact with the Chandrayaan-1 lunar orbiter, a cube-shaped spacecraft less than half the size of Eagle.

And yet in 2016, scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena found it again using radar aimed at a point in space just above the lunar surface where the spacecraft was expected to pass.

When it was lost, Chandrayaan-1 was in a polar orbit, passing above the North and South Poles. Sure enough, the spacecraft turned up as expected.

Meador says a similar technique could find Eagle. In this case, the spacecraft is in an equatorial orbit about 125 kilometers above the surface; aiming a radar just above the lunar limb could spot it. “Four judiciously chosen, two-hour observation periods should provide sufficient coverage to possibly relocate one of the most important artifacts in the history of space exploration,” he says.

Over to the radar scientists at JPL, should they have a few hours to spare. That would be a spectacular find.

Reference: Long-term Orbit Stability of the Apollo 11 “Eagle” Lunar Module Ascent Stage : arxiv.org/abs/2105.10088