The Iberian lynx, the world’s most endangered wildcat species, once numbered fewer than 200 in the wild. Now, more than 300 roam the Iberian Peninsula on Spain’s southernmost tip. And late last year, Portugal welcomed its first pair of lynxes that were reintroduced into the wild from captivity.

The species owes much of its revival to the Iberian Lynx Conservation Breeding Program, which has reintroduced more than 70 lynxes since 2010. But the program got a key assist from an unlikely source: the bloodsucking triatomine assassin bug.

Female lynxes new to pregnancy and motherhood often lose their first litter because of inexperience and stress. So scientists track all females in the program to identify and monitor pregnant lynxes. The problem: They needed blood samples, but tranquilizing the cats to collect blood with a syringe could induce stress and increase risk of abortion.

“We couldn’t [safely] test for pregnancy at all,” recalls Katarina Jewgenow, a reproduction biologist collaborating with the program. So Jewgenow’s colleague at the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research in Berlin, conservation biologist Christian Voigt, suggested using triatomine bugs.

The bugs prick animals with their hollow, needle-like mouthpart, or proboscis, which injects pain-blocking, anti-clotting chemicals. It’s 30 times thinner than standard syringe needles. Plus, the bugs are bigger than mosquitoes, so they can draw more blood and are easier to handle — the perfect syringe substitute.

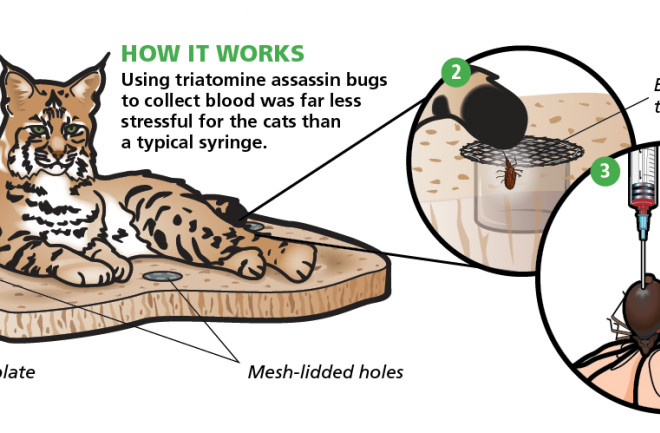

To collect lynx blood, Jewgenow placed the bugs into mesh-lidded holes in large cork plates that lined the lynxes’ den floor. Whenever a lynx rested on a plate, the bugs feasted through the mesh. Jewgenow then collected the plates and extracted the blood from the insects’ swollen abdomens.

This system worked for years until the team developed the fecal pregnancy test it uses today. Who would have thought these little bloodsuckers could help endangered wildcats return to their European homes? Not the lynxes; they never felt a thing. And that was the point.

[This article originally appeared in print as "No Needles Necessary."]